June 10, 2019

Injury Management

Sports Performance

Team Sports

EVALUATION OF THE INTERNAL LOAD IN FOOTBALL: FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE

The development of elite sports has meant that players are constantly exposed to higher training loads, busier competition schedules and shorter rest periods. This has led teams to explore the latest technological and scientific advances in the field of sports medicine in their quest to reduce injury risk without undermining performance.

Monitoring training load (TL) has become essential to planning and scheduling training, optimising physical conditioning and avoiding injury risk. TL is usually categorised as external or internal, defined respectively as the work performed by the athlete (e.g. distance covered, number of accelerations) and the associated physical response (e.g. rating of perceived exertion, heart rate, lactate concentration).

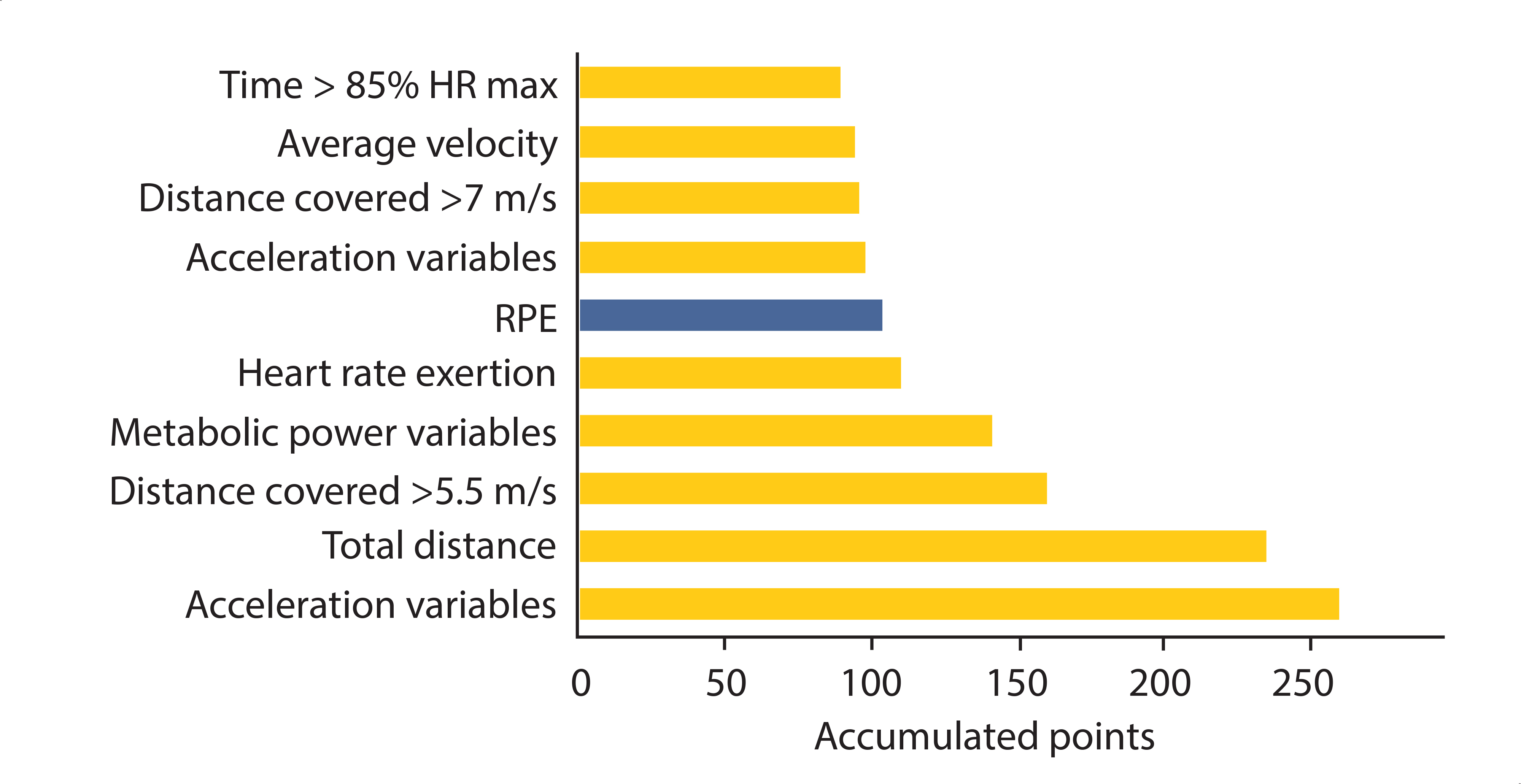

In 2016, a study analysing the main variables used by different professional football teams in order to monitor workload was published (Akenhead & Nassis, 2016). The variables used most often to quantify external and internal load were data from global positioning (GPS) and the rating of perceived exertion (RPE), respectively.

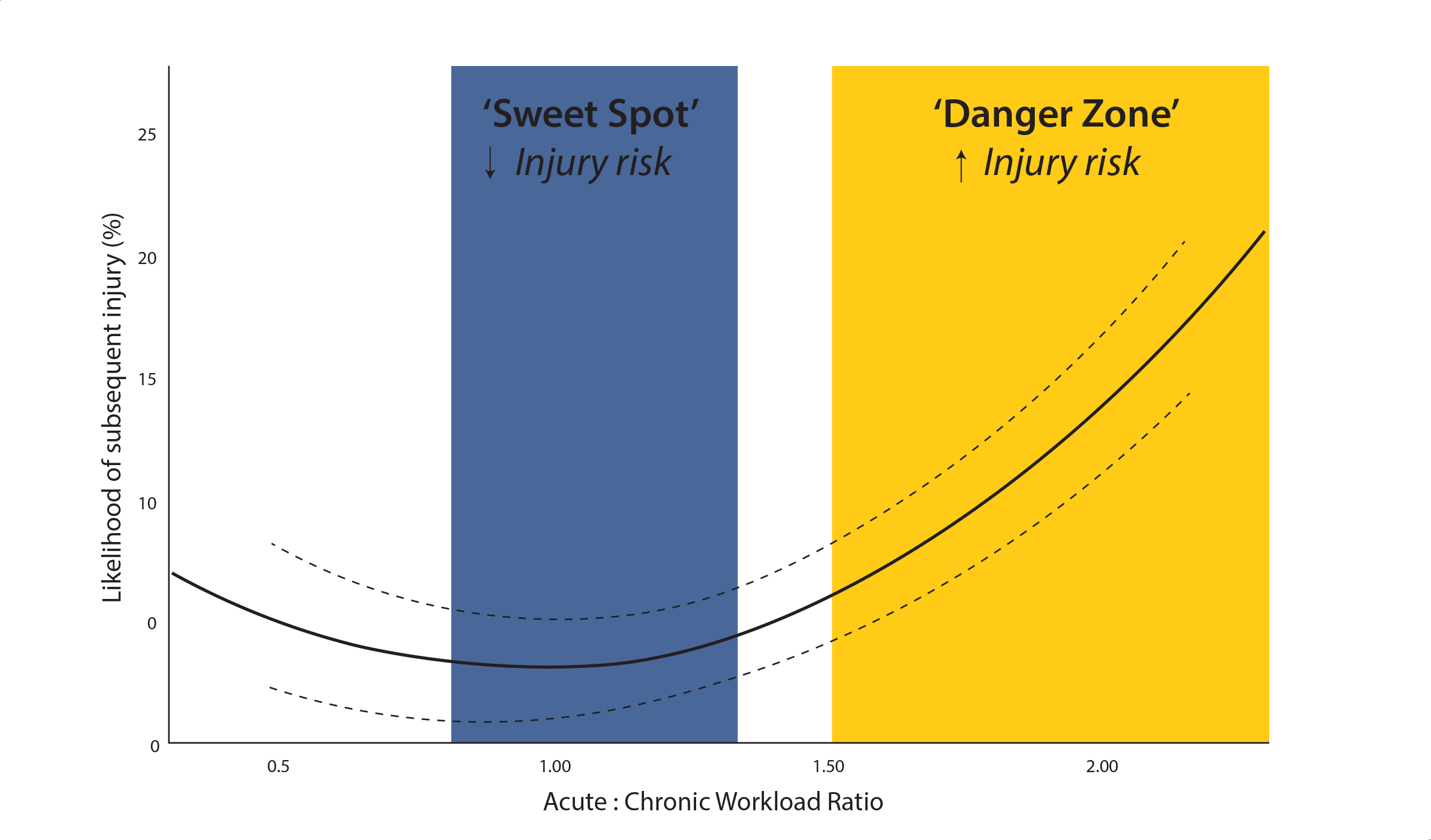

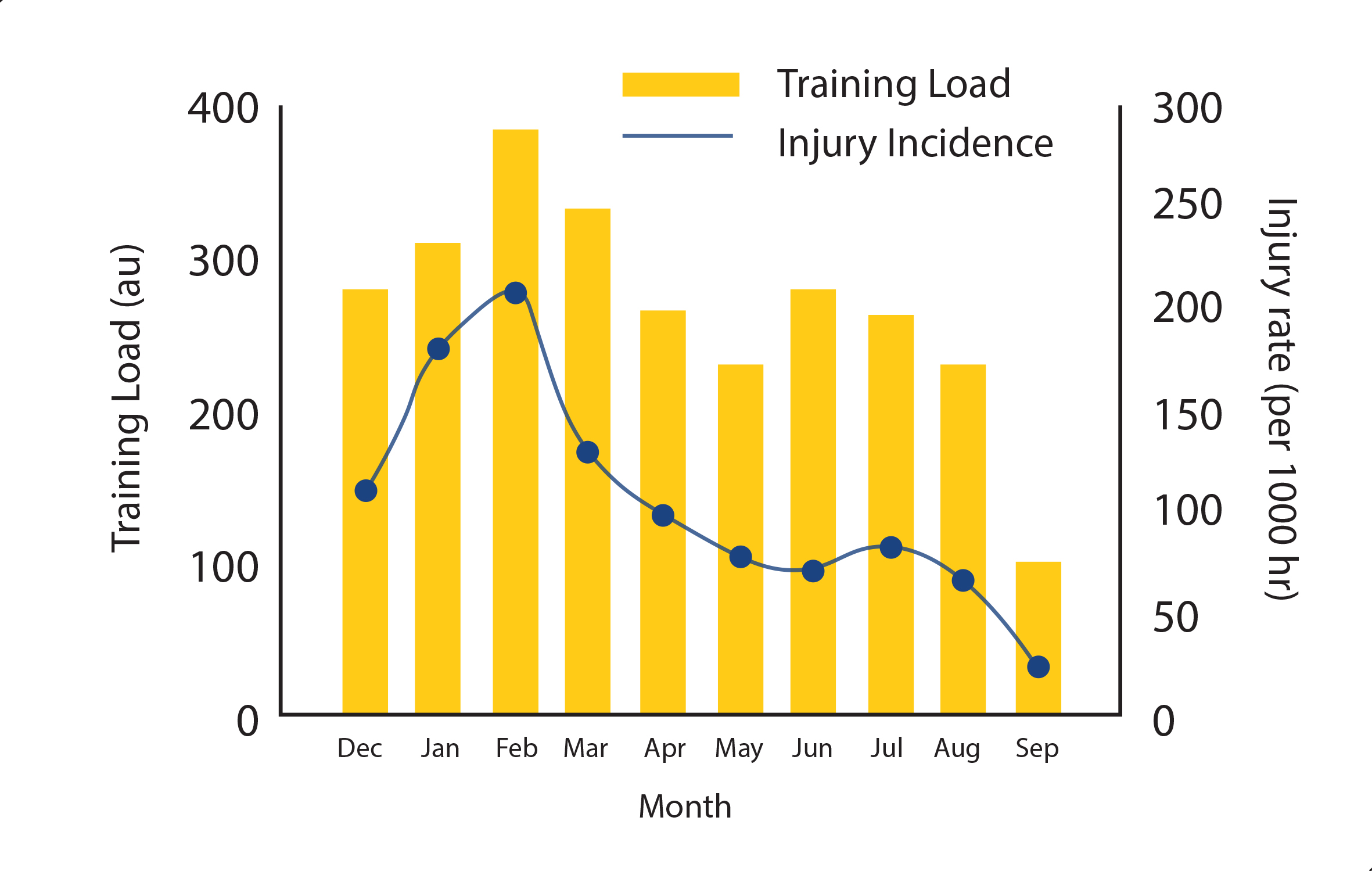

RPE has shown itself to be a precise and easy-to-use tool whereby sportspeople subjectively evaluate the intensity of the session they’ve just completed using values from 1 (rest) to 10 (maximum effort). Monitoring internal load through RPE (RPE x training minutes) has proved to be a valid tool for reducing injury risk and optimising performance. For example, a study of rugby players showed that greater training loads were associated with increased injury risk (Gabbett, 2004).

The physical perception of effort results from the interaction of multiple factors:

- Biological: hormones, neurotransmitter concentration, energy substrate levels (e.g. glycogen), etc.

- External: environment, spectators.

- Psychological state: previous experience, stress, etc.

So as Xavier Franquesa, physical trainer for FC Barcelona’s Juvenile B football team, explains: “Although it’s an easy value to manage, its multifactorial nature means that instructions are needed to use RPE correctly.” In fact, FC Barcelona’s youth football teams start working with this tool; it’s made clear to players that the value to be reported is not shared and does not affect the lineup decision. “The information is only used for performance analysis and medical evaluation. The physical trainer records it, analyses it and connects it to the information on external load, in order to evaluate possible mismatches between external and internal load”, says Marc Guitart, physical trainer for Barça B.

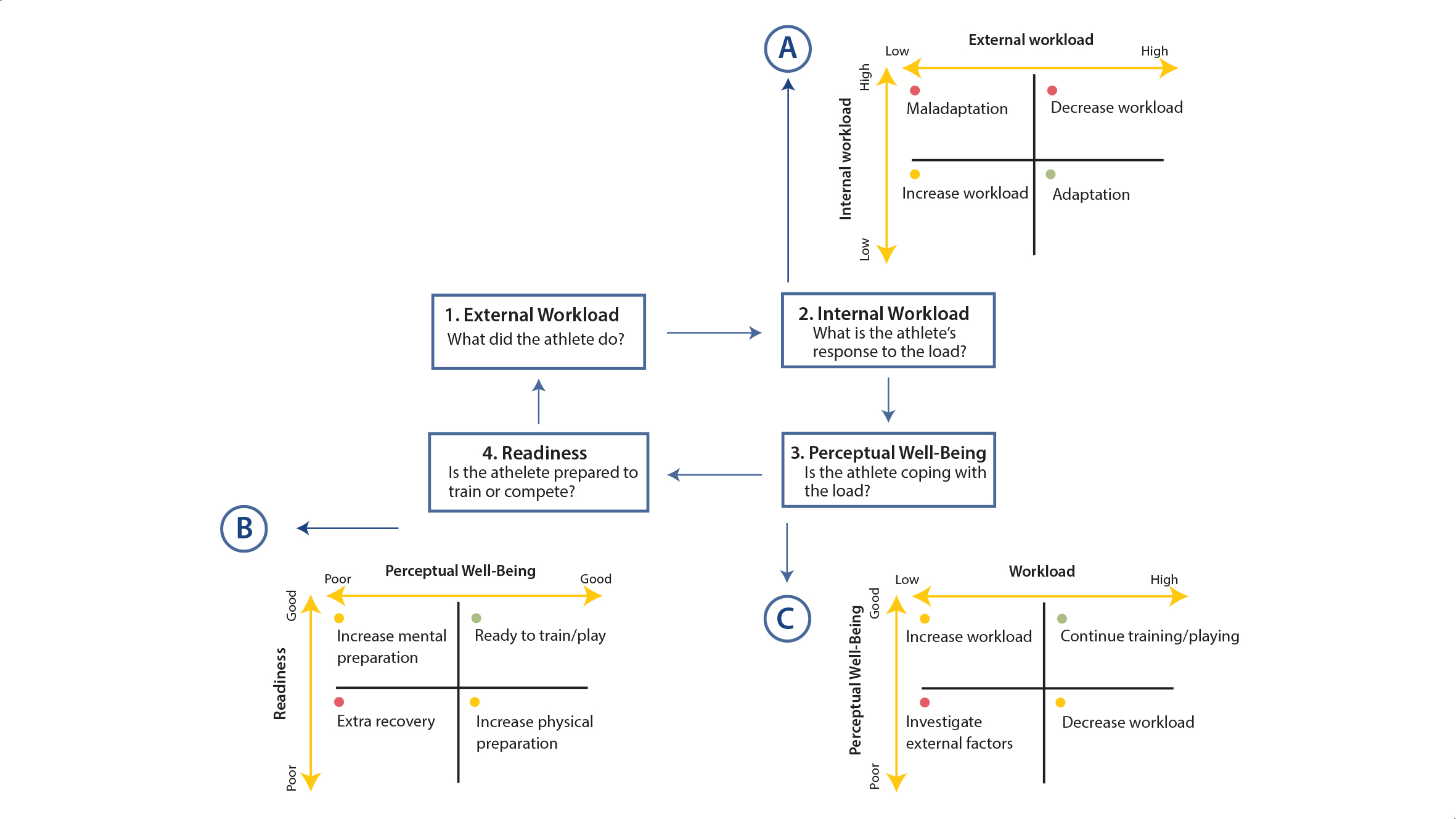

The procedure is the same at all levels. As soon as players arrive at the facility and before beginning their training, they complete a questionnaire on sleep quality, muscle pain and fatigue using a mobile app (eKeep for youth teams and FCB Team for Barça B). These parameters are analysed by physical trainers, doctors and physiotherapists together with the data obtained from the previous day’s session. This information is used to determine whether individual modifications are needed to the day’s proposed training load. As soon as the session ends, the players have a half-hour window in which to assess their perceived exertion during that training session. This data is analysed in conjunction with GPS values to obtain a correlation between internal and external load. If a player has an inverse relationship between the two loads (e.g. low external load and high internal load), the player’s earlier data is examined in order to rule out false alarms and to identify possible courses of action to reverse this status (Figure 3).

As Marc Guitart explains, “the data does fluctuate, so if there’s an occasional red flag, you need to pay attention and put it into context. The objective is to make the trainer’s job easier. Normal conditions don’t need to be addressed. The trainer receives a filtered, individual report on the specific players whose data raised a red flag, and then works on correcting it”.

“The integrated analysis of large quantities of data obtained from training and games–up to 200 variables analysed per player–allows us to develop an overall map of a player’s fitness and relate it to their chronic load, reduce their injury risk and optimise their performance”, says Xavier Franquesa.

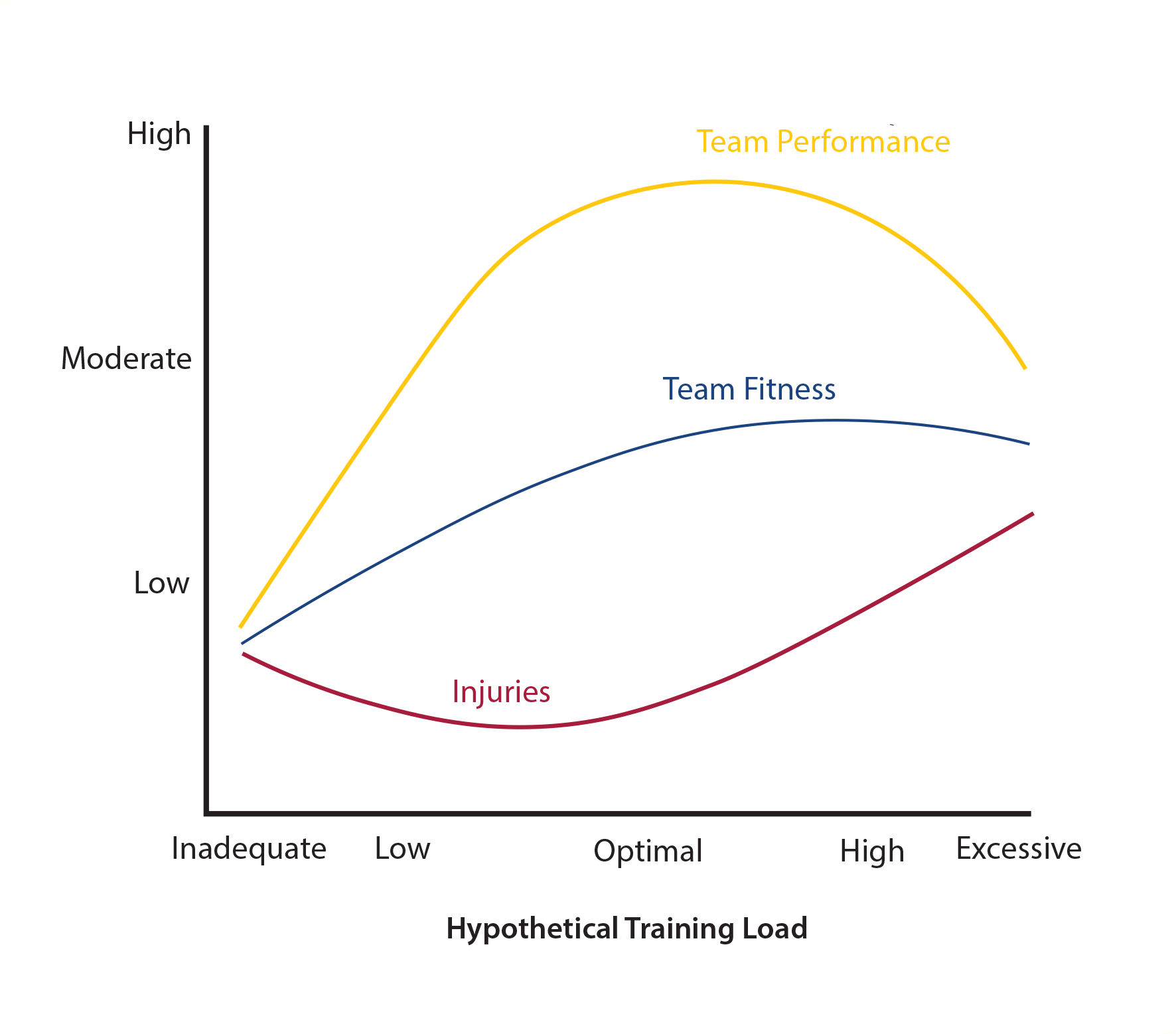

In the physical training field, there’s a core belief that a greater training load leads to higher injury rates. However, there’s also evidence that training has a protective effect when it comes to injuries. The athlete must be prepared to endure high training loads, so it’s critical to incorporate and analyse the greatest number of variables possible in order to find an optimal performance level that does not put a player’s health at risk.

The RPE is an efficient tool for quantifying an athlete’s internal load because it’s easy to implement and its measurements are reliable. The tool’s relationship to external load can help training staff to develop individualised load plans, although it’s important to implement a learning process from the early stages of training.

References

Akenhead, R., & Nassis, G. P. (2016). Training Load and Player Monitoring in High-Level Football: Current Practice and Perceptions. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 11(5), 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0331

Blanch, P. & Gabbett, T. J. (2016). Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(8), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445

Gabbett, T. J. (2004). Influence of training and match intensity on injuries in rugby league. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(5), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410310001641638

Gabbett, T. J., Nassis, G. P., Oetter, E., Pretorius, J., Johnston, N., Medina, D., Ryan, A. (2017). The athlete monitoring cycle: a practical guide to interpreting and applying training monitoring data. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(20), 1451–1452. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097298

Orchard, J. (2012). Who is to blame for all the football injuries. Br J Sports Med.

The Barça Innovation Hub team

KNOW MORE

CATEGORY: MARKETING, COMMUNICATION AND MANAGEMENT

This model looks to the future with the requirements and demands of a new era of stadiums, directed toward improving and fulfilling the experiences of fans and spectators, remembering “feeling” and “passion” when designing their business model.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Through the use of computer vision we can identify some shortcomings in the body orientation of players in different game situations.

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS

A health check must detect situations which, despite not showing obvious symptoms, may endanger athletes subject to the highest demands.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL TEAM SPORTS

In the words of Johan Cruyff, “Players, in reality, have the ball for 3 minutes, on average. So, the most important thing is: what do you do during those 87 minutes when you do not have the ball? That is what determines whether you’re a good player or not.”

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Muscle injuries account for more than 30% of all injuries in sports like soccer. Their significance is therefore enormous in terms of training sessions and lost game time.

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW MORE?

- SUBSCRIBE

- CONTACT

- APPLY

KEEP UP TO DATE WITH OUR NEWS

Do you have any questions about Barça Universitas?

- Startup

- Research Center

- Corporate