August 5, 2019

Performance

Health and Wellness

Medical services and wellness

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TRAINING AND COMPETING IN HEAT

Important sporting events such as the Summer Olympic Games, the football World Cup and the tennis Grand Slam all take place in summer under hot and humid conditions. In fact, the pre-season of most team sports take place in these conditions, and if you add the post-holiday fitness levels of most players, it makes achieving adequate performance at the beginning of the season even more difficult.

When athletes train or compete in a hot environment, their body temperature increases and a series of mechanisms for eliminating heat are triggered. The most important mechanism is sweating, which may account for up to 80% of the total heat eliminated during exercise. Increased sweating and blood flow to the skin takes place in order to reduce internal temperatures. As a consequence, it decreases the amount of blood that reaches the active muscles. The body tries to compensate for this by increasing heart rate and decreasing blood flow to the organs that are not involved in the exercise. These adaptations cannot be maintained indefinitely; the player’s sweating rate decreases, their body temperature increases and this affects their performance.

The main indicator of an athlete’s thermal load is measured by their core temperature. During a match in hot conditions, the average temperature of a football player is 39°C. Higher levels in individuals who are not well adapted are associated with an increased risk of heatstroke, and so measures must be taken to decrease body temperature. In the 2014 FIFA World Cup, brief rest periods were established for the first time in history so that players could hydrate with cold drinks (~10°C) and refresh themselves with moist towels. Both of these strategies have been shown to be effective in reducing body temperature and physiological stress, thus maintaining their performance level (Chalmers et al., 2019; Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 2014).

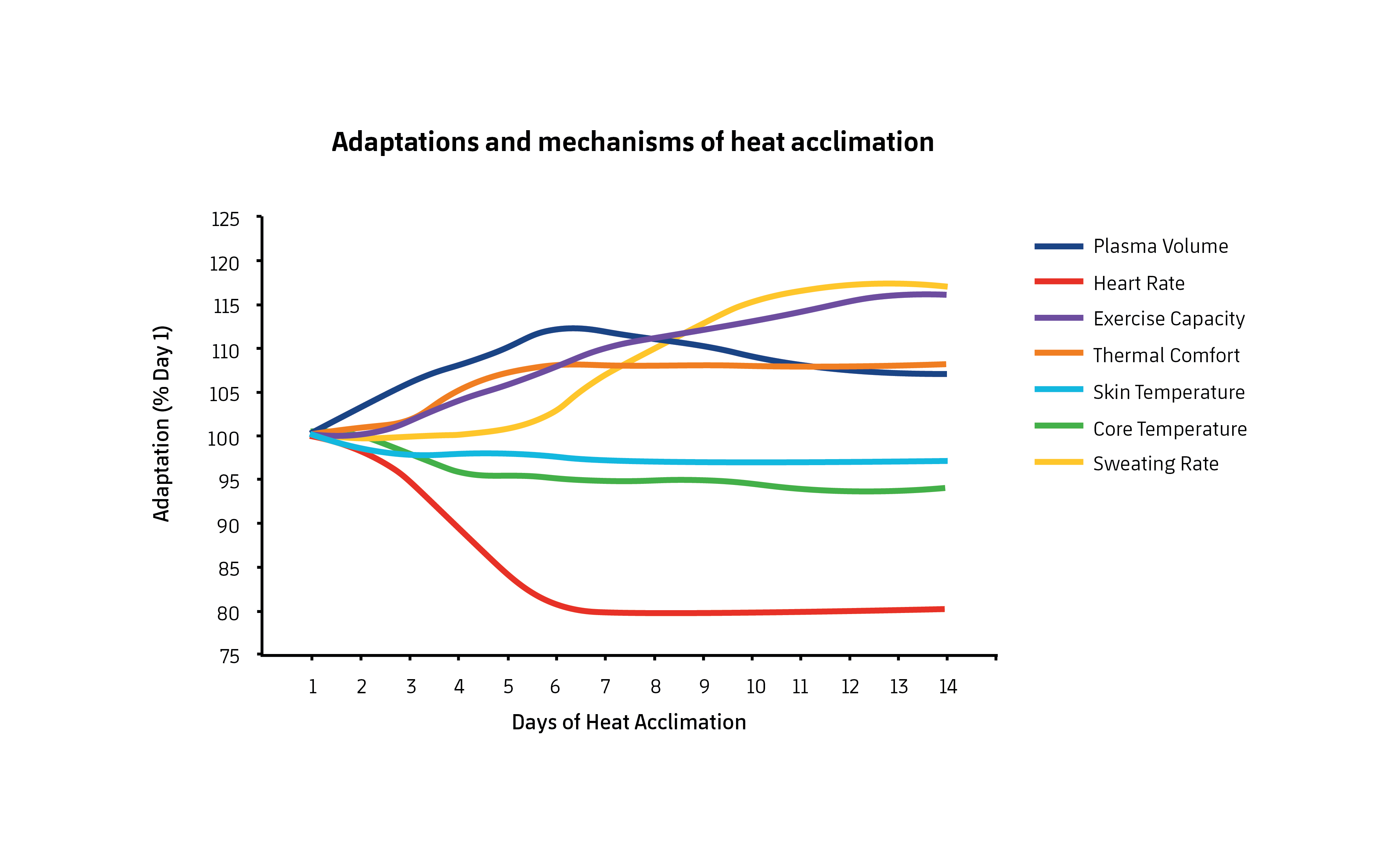

Athletes who are going to compete in hot environments must acclimatise ahead of time by training in heat conditions to obtain different physiological adaptations that minimise their cardiovascular stress and improve their workload ability at increased temperatures. These adaptations are characterised by an increased plasma volume and sweating rate, a lower electrolyte content in the sweat and a lower thermal perception. Heart rate and blood pressure also decrease to submaximal intensities. This leads to less physiological stress and better physical performance when the athlete performs in heat (Verdaguer‐Codina, Martin, Pujol‐Amat, Ruiz, & Prat, 1995)(Figure 1).

Practical recommendations

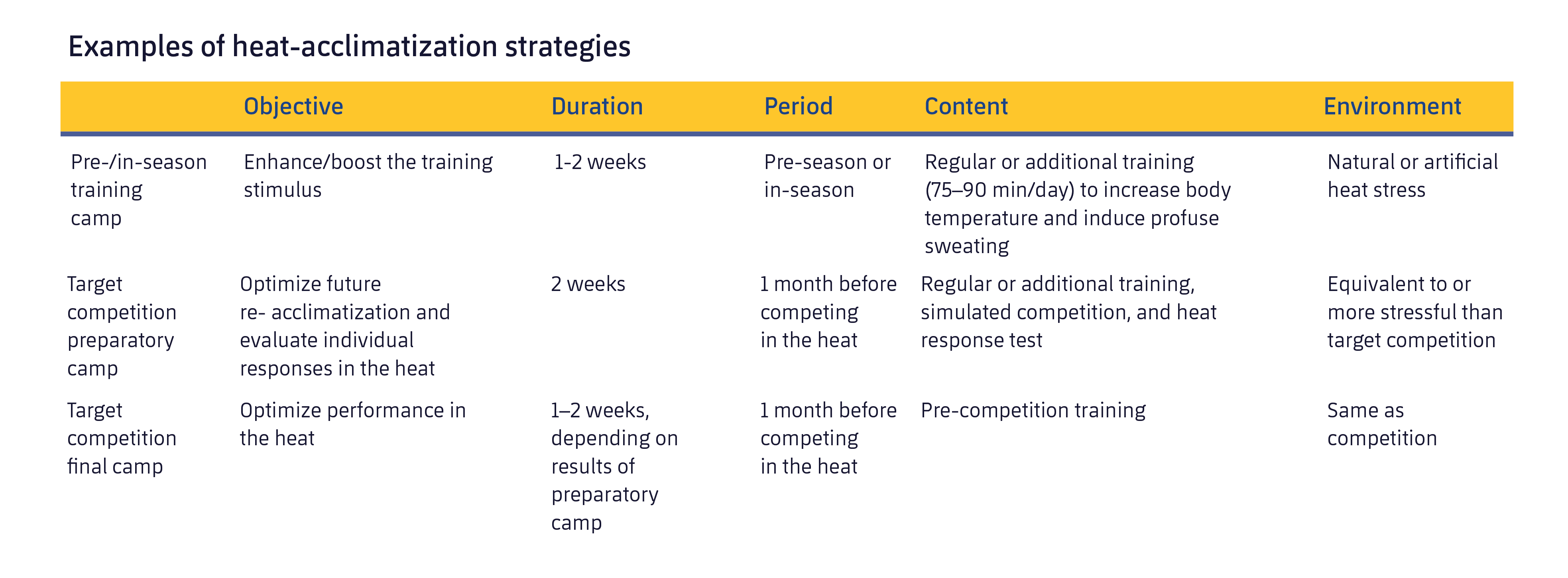

To optimise adaptations, the training sessions during acclimation should last at least 40-60 minutes and be carried out in the same environment in which the players will compete. If this is not possible, the training may be completed in high-temperature rooms in which the humidity can be modified to favour sweating.

Even if the adaptations are achieved in the first few days, the acclimation period should ideally last around two weeks to maximise the benefits. This is especially relevant for women since they need more days to reduce cardiovascular and thermal stress (Mee, Gibson, Doust, & Maxwell, 2015).

The adaptations achieved after an acclimation period last between two and four weeks. These adaptations can be maintained with an intermittent heat exposure protocol, in other words training at high temperatures once every 5-10 days (e.g. 35-40ºC, humidity >40%) during the month following the acclimation period. In this way, the duration of the high-temperature training is decreased and the physiological benefits are extended prior to the competition (Gorostiaga Ayestarán, 2007; Pryor et al., 2019).

In addition to prior heat acclimation, athletes must follow certain guidelines for adequate hydration that help control sweat levels, thus maintaining active thermoregulation during exercise. In the hour before the competition, it is advisable to drink 500 ml of fluids with mineral salts. During the competition, players must hydrate to restore the loss of body water, thereby decreasing cardiovascular stress and helping maintain performance. It is recommended to drink every hour 500 ml of a cold isotonic drink (between 15-21°C) that contains between 40 and 80 grams of carbohydrates, as well as sodium, as this is the main electrolyte in sweat. It may be necessary to supplement this to maintain sodium balance in the blood plasma (Gorostiaga Ayestarán, 2007).

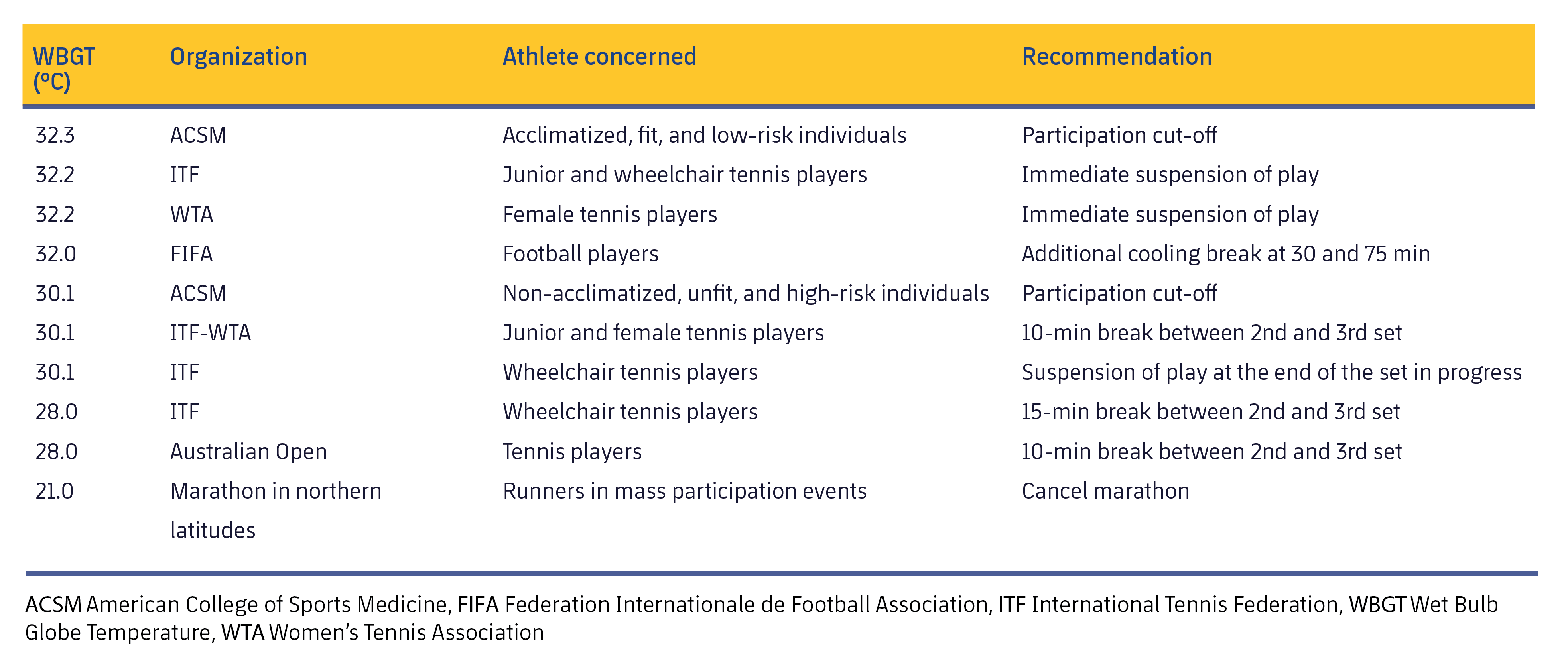

All these strategies aim to minimise physiological stress and optimise performance in hot environments, but they must be accompanied by responsible actions by the organisers of sporting events. In recent years, entities such as the American College of Sports Medicine, FIFA and the International Tennis Federation have made recommendations for exercising in heat based on the WBGT (Wet Bulb Globe Thermometer) Index. This index not only takes into account the environmental temperature, but also heat stress, and estimates the effect of temperature, humidity, wind speed and solar and environmental radiation. On the basis of the WBGT values, different strategies have been implemented ranging from brief pauses during sports activity for athletes to rehydrate and refresh themselves, as well as extending rest periods or even cancelling the match or event (Figure 3).

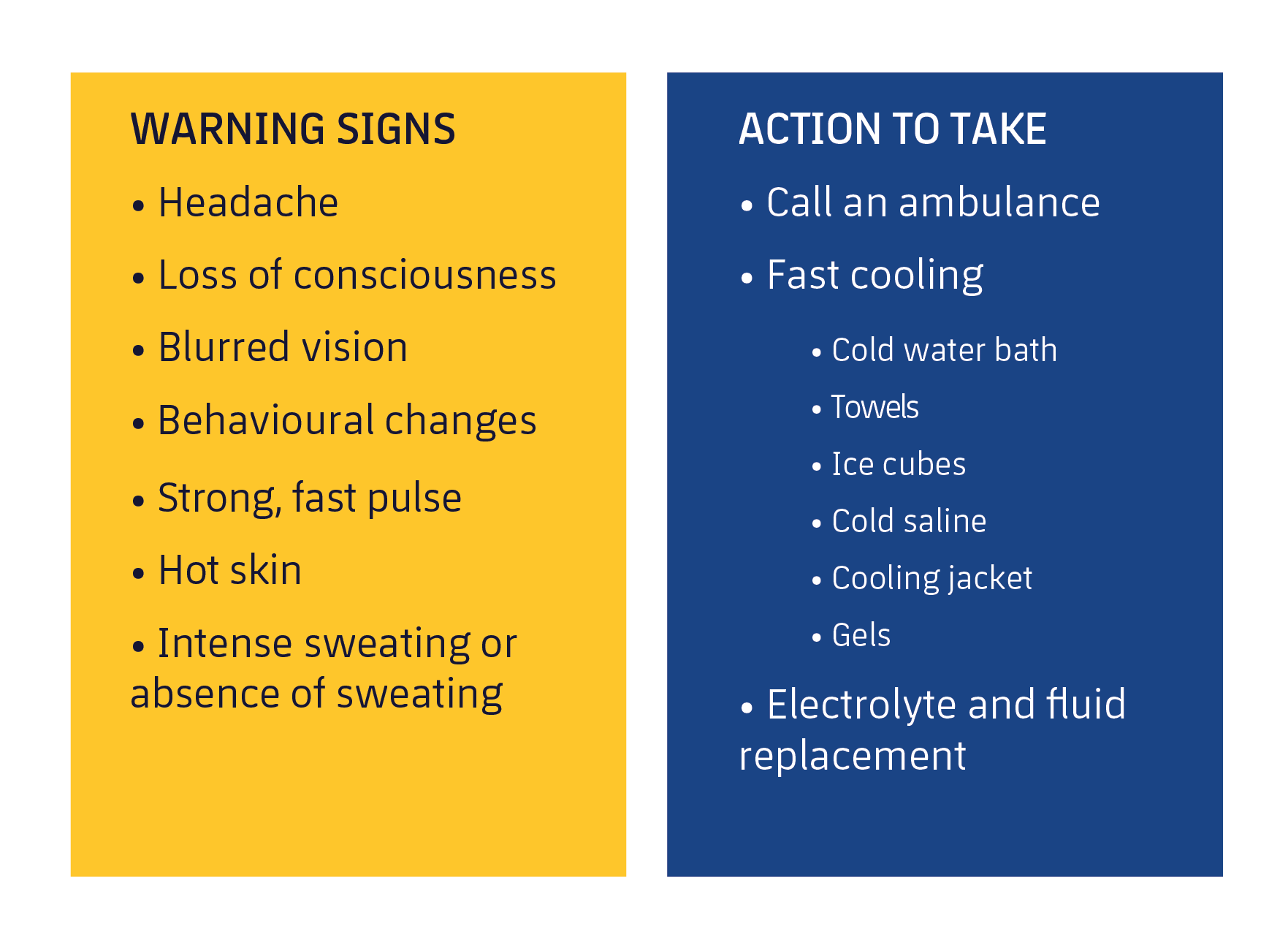

In addition, the coaching staff and doctors must be alert to detect any early warning sign of a heat stroke and know how to avoid it, as well as the action that must be taken to care for a person who is suffering from a heat stroke (Figure 4).

Conclusions

Playing sports in heat decreases performance and increases physiological stress, which can have negative health consequences. Prior acclimation in hot environments is therefore necessary in order to produce adaptations that alleviate cardiovascular stress, and during sports activities, it is important to use methods which reduce body temperature and maintain hydration. This must be accompanied by intervention protocols that minimise the risk of heat stress during exercise.

The Barça Innovation Hub team

REFERENCES

Chalmers, S., Siegler, J., Lovell, R., Lynch, G., Gregson, W., Marshall, P., & Jay, O. (2019). Brief in-play cooling breaks reduce thermal strain during football in hot conditions. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 22(8), 912–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSAMS.2019.04.009

Fédération Internationale de Football Association. (2014). A cool first and a historic triumph. Retrieved July 16, 2019, from https://www.fifa.com/worldcup/news/a-cool-first-and-a-historic-triumph-2390305

Gorostiaga Ayestarán, E. (2007). Adaptaciones al clima y al horario de Pekín’08.

Mee, J. A., Gibson, O. R., Doust, J., & Maxwell, N. S. (2015). A comparison of males and females’ temporal patterning to short- and long-term heat acclimation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12417

Périard, J. D., Racinais, S., & Sawka, M. N. (2015). Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: Applications for competitive athletes and sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25, 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12408

Pryor, J. L., Pryor, R. R., Vandermark, L. W., Adams, E. L., VanScoy, R. M., Casa, D. J., … Maresh, C. M. (2019). Intermittent exercise-heat exposures and intense physical activity sustain heat acclimation adaptations. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 22(1), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.06.009

Racinais, S., Alonso, J. M., Coutts, A. J., Flouris, A. D., Girard, O., González-Alonso, J., … Périard, J. D. (2015). Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25, 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12467

Verdaguer‐Codina, J., Martin, D. E., Pujol‐Amat, P., Ruiz, A., & Prat, J. A. (1995). Climatic heat stress studies at the Barcelona Olympic Games, 1992. Sports Medicine, Training and Rehabilitation, 6(3), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438629509512048

KNOW MORE

CATEGORY: MARKETING, COMMUNICATION AND MANAGEMENT

This model looks to the future with the requirements and demands of a new era of stadiums, directed toward improving and fulfilling the experiences of fans and spectators, remembering “feeling” and “passion” when designing their business model.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Through the use of computer vision we can identify some shortcomings in the body orientation of players in different game situations.

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS

A health check must detect situations which, despite not showing obvious symptoms, may endanger athletes subject to the highest demands.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL TEAM SPORTS

In the words of Johan Cruyff, “Players, in reality, have the ball for 3 minutes, on average. So, the most important thing is: what do you do during those 87 minutes when you do not have the ball? That is what determines whether you’re a good player or not.”

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Muscle injuries account for more than 30% of all injuries in sports like soccer. Their significance is therefore enormous in terms of training sessions and lost game time.

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW MORE?

- SUBSCRIBE

- CONTACT

- APPLY

KEEP UP TO DATE WITH OUR NEWS

Do you have any questions about Barça Universitas?

- Startup

- Research Center

- Corporate