October 20, 2020

Psychology

Nutrition

Medical services and wellness

THE ROLE OF THE NUTRITIONIST AND SPORTS PSYCHOLOGIST DURING INJURY RECOVERY

The first question that almost all players ask after getting injured is: “When will I be able to play again?” The return to the pitch or return to play (RTP) is seen as that magical day in which the player returns to fully enjoy the sport, at the same level or even better than before, as if the injury had never occurred. The RTP is one of the most important aspects in the recovery process of a footballer after an injury since it is the period in which he must prepare for his return to the competition.

The RTP should be seen as a continuum throughout the entire recovery and rehabilitation process.1 A Consensus Statement published in 2016 on the athlete’s RTP after an injury proposed three phases within this continuum:1

- Return to Participation: the athlete can return to perform complete or partial training sessions, but is not yet medically, physically, or psychologically ready to return to the sport practice.

- Return to Sport: the athlete is fully integrated into his sport, but not at the desired level of performance. He usually participates in all training sessions.

- Return to Performance: when the athlete has reached or even exceeded the level of performance prior to the injury and he is ready to compete.

In these cases, an interdisciplinary approach will allow players in their RTP to be physically and psychologically prepared to do so with a minimal risk of relapse, as this is a critical time for the appearance of new injuries. In fact, the 2016 Consensus Declaration recognised the important contribution of other disciplines, apart from medicine and physiotherapy, such as sports science or coaching.1 Likewise, the document established the importance of considering biopsychosocial factors during the whole process of RTP.1 That is why it is considered essential to integrate psychology and sports nutrition within the interdisciplinary approach necessary to achieve a full recovery and a successful RTP.

A review article has just been published in which members from FC Barcelona’s medical services and performance area have taken part, which analyses the role of psychology and sports nutrition within the RTP process after an injury.2 The authors differentiate between the acute injury phase and the functional recovery one.

Acute injury phase

During this phase (from the moment the injury takes places until the start of active mobilisation of the injured area, which would coincide with the Return to Participation), doubts and fears frequently appear regarding the severity of the injury. Thoughts such as “I will never regain my best level; Why me? Why now?”, and negative emotions (frustration, anger, hopelessness) that can even increase the perception of pain. All of these thoughts and emotions can contribute to increase the feelings of distress and anxiety. For this reason, the sports psychologist is important within the medical department of the team, as relaxation techniques, diaphragmatic breathing or the use of images can mitigate the responses to pain and the corresponding feelings of anguish.

From a psychological point of view, respecting the period of inactivity inherent in injuries can be particularly distressing for players. Sports psychologists, together with the rest of the medical team, must work collaboratively to mitigate and alleviate this anguish, apart from using a lot of pedagogy with the player and providing clear and coherent information on the importance of respecting the times that every injury requires. It is essential to work on these aspects, as the uncertainty about the injury diagnosis (severity, implications) and doubts about the efficacy of the treatment received are important predictors of adherence to treatment.

The player must be involved throughout the process, making him a participant in the decisions regarding the treatments to follow, offering him different alternatives and treatment options whenever possible, and showing him in such cases that his opinion is taken into consideration. It has been observed that following this procedure, the player reinforces his autonomy and control within the recovery process.3 This issue is not trivial, as during the acute phase of recovery, players may feel a lack of control over their own bodies, which can endanger the course of recovery.

Moreover, during this phase, the nutritional plan must complement the physical rehabilitation. Nutritionists and sports psychologists have to work closely together in order to identify those players who may be at risk of developing eating disorders (bulimia, anorexia, etc.) or body dissatisfaction with the risk of weight gain, so as to treat these problems if they arise. It will also be essential to provide players with a diet that ensures enough energy to maintain muscle mass and minimise damage from inactivity.

Energy expenditure could be even higher during this acute phase of injury as a result of the healing process in combination with rehabilitation during the initial phase. Consequently, it is recommended not to reduce the total caloric intake below 2,750 kcal during this phase, recommending a range between 2,750 and 3,250 kcal, depending on the level of immobilisation of the athlete. For instance, the case of an injured Premier League player (rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament) who consumed 3,178 kcal per day4, which is just a little less than the 3,500 kcal consumed on average by team mates in a two-game week, has just been published.5 While reducing carbohydrates may be required, again depending on the level of immobilisation, a study of another Premier League player showed that a low-carbohydrate diet resulted in the loss of almost 6 kg of muscle mass and a gain of 1 in fat mass in just 8 weeks of inactivity.6 What should be avoided is that injured players reduce their protein intake during the recovery process. It would even be recommendable to increase daily protein intake to 2.3 g/kg of weight to prevent muscle mass loss.

Other recommendations to follow in order to reduce muscle atrophy secondary to immobilisation would be the consumption of fish oil supplements rich in omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D3, and creatine monohydrate.2 Finally, although sports psychologists should not provide nutritional information, nutritionists could advise psychologists to reinforce certain messages to players so that they adhere to nutritional guidelines.2 Gelatine and collagen are rich in glycine, proline, hydroxylysine and hydroxyproline, and their consumption has demonstrated to increase collagen synthesis and improve the ligament and tendon mechanics. For injuries to the myotendinous junction, the intake of hydrolysed collagen may be advisable before the rehabilitation session so as to help facilitate the healing process.7 Once the player can begin to train again, they should focus on the “basics” of sports nutrition: begin exercise with adequate reserves of muscle glycogen and being well hydrated.8

Also, during the injury period it is advisable to eliminate, or reduce as much as possible the consumption of alcohol. Alcohol reduces protein synthesis, even if taken in conjunction with protein, which can affect recovery.9 Besides, alcohol increases the risk of excessive caloric intake and failure of psychological strategies.

Functional recovery

This phase would correspond to Return to Participation.

A serious problem during this phase is the player’s ability to seek motivation, especially in the case of long-term injuries. Motivation within the RTP process plays an important role, as on many occasions the player himself questions his performance after an injury and, therefore, all what’s related to motivation must be adequate in order to restore the confidence after a long period of inactivity.

There are also concerns about their ability to cope with a tough rehabilitation, with exercises that will lead the player to explore their physical and mental limits. Feelings of isolation from being removed from the team’s routine will also have an impact on the players during functional recovery. Keeping the injured player connected to the rest of the team can help him feel important and increase his sense of belonging to the group.10 This can be accomplished by including him in game review meetings and even attending team meals.

Another factor to take into account for serious injuries, is that the player may even consider if he will ever recover or if he will be able to reach his maximum performance again, which can lower his self-esteem (“I am nobody without football, it’s the only thing I’m good at“). Therefore, during this phase, showing him the experience of other similar cases that managed to recover their best shape after a similar injury will allow the player to convince himself that it is possible to return to elite sports again.

Conclusions

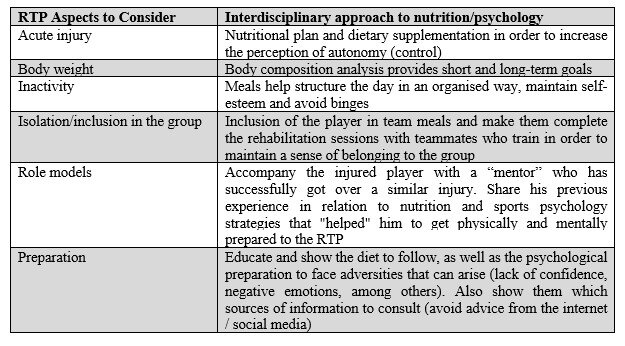

Nutritional and psychological follow-up during injury often makes players, who have been reluctant to work with specialists in these disciplines, get involved for the rest of their careers, giving them great benefits (Table 1). Providing players with the proper nutritional guidelines and psychological “tools” to manage the injury process may also remain relevant once the player has overcome the injury. Also, it will serve as a preventive measure against a relapse.

It is essential that we understand the RTP as a continuous decision-making process, where each decision taken will condition the following. In this sense, an interdisciplinary approach will always be the most suitable strategy to avoid taking false steps. And although sports clubs increasingly include nutritionists and sports psychologists in their staffs, there is still much to be done for the great value they can bring to the team.

Javier S. Morales

References:

- Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):853-64.

- Rollo I, Carter JM, Close GL, Yangüas J, Gomez-Diaz A, Medina Leal D, Duda JL, Holohan D, Erith SJ, Podlog L. Role of sports psychology and sports nutrition in return to play from musculoskeletal injuries in professional soccer: an interdisciplinary approach. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020.

- Chan DK, Lonsdale C, Ho PY, Yung PS, Chan KM. Patient motivation and adherence to postsurgery rehabilitation exercise recommendations: the influence of physiotherapists’ autonomy-supportive behaviors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(12):1977-82.

- Anderson L, Close GL, Konopinski M, Rydings D, Milsom J, Hambly C, Speakman JR, Drust B, Morton JP. Case Study: Muscle Atrophy, Hypertrophy, and Energy Expenditure of a Premier League Soccer Player During Rehabilitation From Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(5):559-566.

- Anderson L, Orme P, Naughton RJ, Close GL, Milsom J, Rydings D, O’Boyle A, Di Michele R, Louis J, Hambly C, Speakman JR, Morgans R, Drust B, Morton JP. Energy Intake and Expenditure of Professional Soccer Players of the English Premier League: Evidence of Carbohydrate Periodization. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2017;27(3):228-238.

- Milsom J, Barreira P, Burgess DJ, Iqbal Z, Morton JP. Case study: Muscle atrophy and hypertrophy in a premier league soccer player during rehabilitation from ACL injury. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2014;24(5):543-52.

- Baar K. Minimizing Injury and Maximizing Return to Play: Lessons from Engineered Ligaments. Sports Med. 2017;47(Suppl 1):5-11.

- Williams C, Rollo I. Carbohydrate Nutrition and Team Sport Performance. Sports Med. 2015;45 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S13-22.

- Parr EB, Camera DM, Areta JL, Burke LM, Phillips SM, Hawley JA, Coffey VG. Alcohol ingestion impairs maximal post-exercise rates of myofibrillar protein synthesis following a single bout of concurrent training. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88384.

- Podlog L, Heil J, Schulte S. Psychosocial factors in sports injury rehabilitation and return to play. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(4):915-30.

KNOW MORE

CATEGORY: MARKETING, COMMUNICATION AND MANAGEMENT

This model looks to the future with the requirements and demands of a new era of stadiums, directed toward improving and fulfilling the experiences of fans and spectators, remembering “feeling” and “passion” when designing their business model.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Through the use of computer vision we can identify some shortcomings in the body orientation of players in different game situations.

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS

A health check must detect situations which, despite not showing obvious symptoms, may endanger athletes subject to the highest demands.

CATEGORY: FOOTBALL TEAM SPORTS

In the words of Johan Cruyff, “Players, in reality, have the ball for 3 minutes, on average. So, the most important thing is: what do you do during those 87 minutes when you do not have the ball? That is what determines whether you’re a good player or not.”

CATEGORY: MEDICINE HEALTH AND WELLNESS SPORTS PERFORMANCE

Muscle injuries account for more than 30% of all injuries in sports like soccer. Their significance is therefore enormous in terms of training sessions and lost game time.

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW MORE?

- SUBSCRIBE

- CONTACT

- APPLY

KEEP UP TO DATE WITH OUR NEWS

Do you have any questions about Barça Universitas?

- Startup

- Research Center

- Corporate